In the summer of 2015, before starting my third year at Pomona College, I decided to hike the Pacific Crest Trail. More specifically, I decided that a long walk along the western geological spine of the continental United States from Mexico to Canada was a goal that could not be left to slowly erode over time under the constant ebb and flow of career, family, and responsibility. The gravitational pull to hiking the Pacific Crest Trail was the challenging and minimalistic nature of the journey while gaining access to some of the most remote, diverse, and awe-inducing land the United States has to offer.

Of course, it all sounded lovely and romantic and Thoreau-esque, navigating deserts and mountain ranges while sleeping under the Milky Way, so it was inevitable that the first couple weeks on trail would be a primer as to what exactly life outdoors entailed. From those first steps departing the Mexican border, I often found myself hiking alone and camping with a new group almost every night. The long days of isolation permeated an inescapable sense of my aloneness. The land, which altered daily as the trail oscillates from desert valley floor to rocky mountain ridge, offered little sense of home.

After hiking a few hundred miles, the desire for kinship overtook my stubbornness to not sacrifice hiking pace, and I met my first trail family in Frodo and Everest. As our smelly family grew, with people named Saint Bernard, Good News, Bear, Bear Can, and Hot Sauce, it rapidly became evident that the people on the trail provided the sense of home-ness and camaraderie I was initially missing. Ultimately I found, the fellow hikers served as my greatest source of joy, in getting to share the daily ups and downs, excitement and boredom with them. The last month and a half was particularly challenging as I spent nearly all of the time alone (except for the section from Etna to Ashland with Roadrunner), and it cemented the notion that experiences are most rewarding and fulfilling when shared with people you care about.

Back when the idea of a PCT hike had more figurative than literal meaning, I approached the Gustafson family about helping to fundraise for pediatric brain cancer research through the Swifty Foundation. The prospect of combining my love of science with that of the outdoors was greatly appealing and added another dimension of personal meaning to the journey. Yet, like most other aspects of a hike from Mexico to Canada, I did not fully appreciate the role being involved in the pediatric brain cancer community would play in my day-to-day life on trail. Little could I have predicted the profound impact the Four Pennies campaign, from the four foundations that came together to spearhead fundraising to the bench-side work it supports through Open DIPG (and the Children’s Brain Tumor Tissue Consortium and the Children’s Brain Tumor Project), would have.

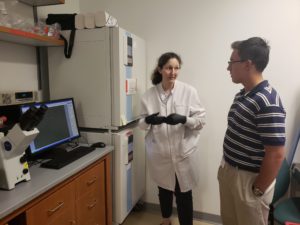

A long hike requires the commitment to being removed from the meaningful interactions of life for an extended period of time. It may sound enticing, to be detached from the daily news cycle, but as the days turned to months, a discontent burgeoned that I came to recognize as a lack of satisfaction in my emotional need to feel that what I was doing was worthwhile for someone other than myself. That is why getting the opportunity to see the work being done at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and at the Weill Cornell Brain and Spine Center was immeasurably gratifying, and quite honestly left me speechless. To see the cancerous cell lines–live cells maintained in the lab for future study and generated from tissue donations via patient tumor biopsy–the groups had established was overwhelming.

Each cell, which could be seen clear as day under the microscope, was the fundamental unit of a living human being. In each of these cases, that human was a child who drew the short straw of a having a minute alteration in their genetic code, which drove a small cohort of cells in the brain into cancerous overdrive. The gravity of the meaning each cell line carried, to the parents of the child, to the researchers, and to the field as a whole, was palpable. As I look forward to the start of medical school at the University of Texas, Southwestern, I cannot help but envision myself alongside those doctors and researchers, families and patients. The topic of my future specialty was one of frequent thought on the trail, even talking to myself aloud when I was particularly lonely, and I am hard-pressed to think of anything more gratifying than being able to treat children, to meet them at that most vulnerable moment and to see them live full, complex, meaningful lives.

I now know, all those long days, the nights spent alone with only the company of the galaxies, it was all worth it, and for that, I sincerely thank each and every person who made the visits possible.

thanks,

Eric